What is an A-3 Report?

REFLECTION: FOR STUDENTS: “Having no problems is the biggest problem of all.”- Taiichi Ohno

FOR ACADEMICS: “Data is of course important in manufacturing, but I place the greatest emphasis on facts.”- Taiichi Ohno

FOR PROFESSIONALS/PRACTITIONERS: “Make your workplace into showcase that can be understood by everyone at a glance.”- Taiichi Ohno

Foundation

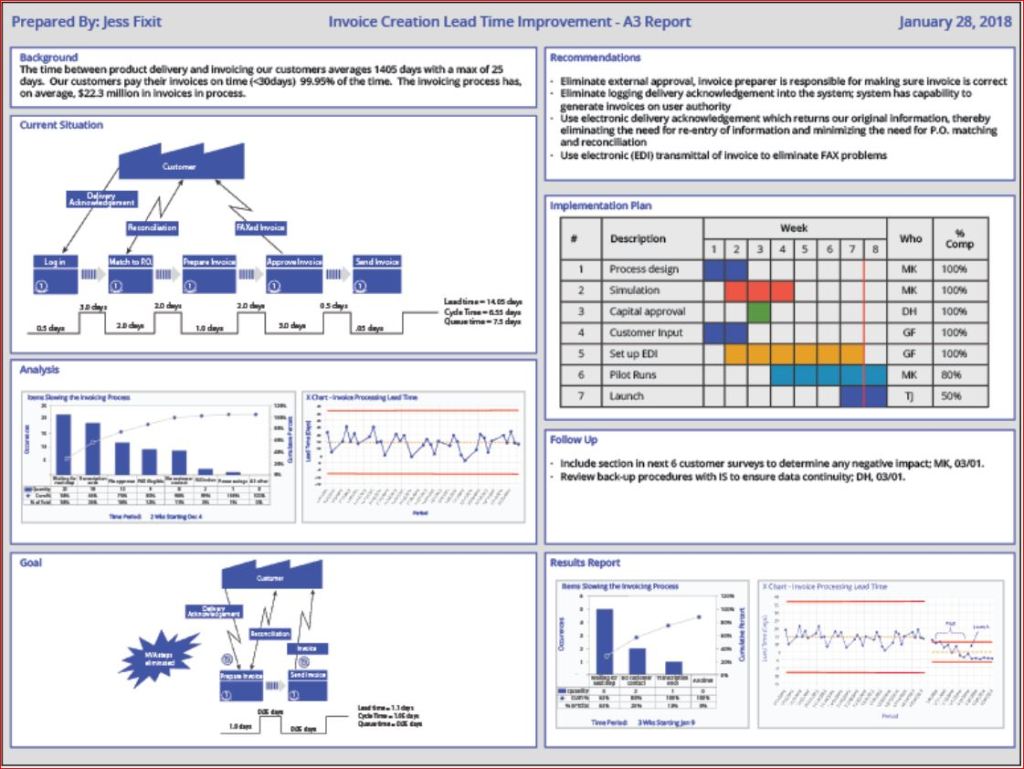

The A3 Report is a model developed and used by Toyota and currently used by many businesses around the world. The A3 Report is named for a paper size-A3 (29.7 x 42.0cm, 11.69 x 16.53 inches). The entire current state and PDCA aspects of the project are captured visually for easy communication and reference. When CIP projects use an A3 methodology to track projects, it has been demonstrated that clear visual communication helps the team members and the overall organization be more aware of the team’s progress.

A minor improvement event, in my experience, is generally four weeks to six weeks. Still, when an issue needs to be addressed thoroughly, the organization must be willing to invest more time and resources. Almost every moment of improvement time spent may be wasted if the true root cause is not adequately addressed due to failure to properly invest resources. There are four distinct phases: 1) preparation and training; 2) process mapping and current state analysis; 3) process mapping and future state analysis; and 4) implementation and ownership. I will put up a basic template below and walk through the A3 report.

Example

- Clarify the Problem

- IS/IS Not Analysis-excellent first tool to use to define the scope of the problem.

- After the scope of the problem has been defined, define the problem relative to the organization or process. The focus should always be on an underlying process or systematic issue, not an individual failure. Systematic failures are frequent but can be corrected with teamwork. The problem statement should never include a suggestion for a solution.

- Breakdown the Problem

- Clearly define the problem in terms of the 5 Why’s and 2 W’s (Who?, What?, When?, Where?, Why? And How?, How much or often?

- Set goals for improvement towards the ideal state vs current state

- Team sets S.M.A.R.T. goals relevant to block 1 state, establishing the end improvement target

- Root Cause Analysis

- Team uses focus areas from block 2 to determine Root Cause(s) employing relevant RCA tools

- Common RCA tools

- Cause-Effect/Fishbone Diagram

- 5 Why Analysis

- Fault Tree Analysis

- Pareto Chart

- Clearly state the determined root cause(s) and display the output of the tools

- Develop Countermeasures

- The team should take the root cause/causes from Block 4 and assign specific countermeasures.

- Countermeasures should directly address the root cause and, in theory, should solve the problem identified in Block 1.

- The completed fifth block is populated with any tool that will outline the countermeasures.

- Implement Countermeasures

- The team tracks the countermeasures from Block 5 and ensures each one is accomplished.

- The completed sixth block should be populated with the tool used in Block 5 to outline the countermeasures and updated as each is accomplished.

- Monitor Results and Process

- Effectiveness Check of Countermeasures

- Before/After Analysis

- SPC Control Charts

- Use Data from block 1 to determine if countermeasures from block 5 are having the desired effect relative to the target.

- If countermeasures are not effective, go back to RCA-block 4 (PDCA) and reconvene.

- Use the tool from block 6 to track countermeasure as ineffective in Block 7

- Effectiveness Check of Countermeasures

- Standardize successful processes

- If countermeasures are effective-

- Standardize all successful processes and note successful countermeasures as Standardized as they are approved using the tool from block 6 in Block 7

- A separate block can be used for Standardized processes

- If countermeasures are effective-

Conclusion

A complete A3 report can use many different tools, depending upon the problem being examined, so don’t fall into the habit of always using the exact same format. Be certain all four phases are completed. Innovation comes from creativity, so leave behind SOPs that demand exact clones of past reports. You may be dealing with a problem no person in your organization has yet to encounter, so outside of the box is thinking should always be on the table (Not locked away in a closed mind)

Bibliography

Quality Management Journal, Volume 16, 2009 – Issue 4

Published Online: 21 Nov 2017

Quality Progress Volume 49, 2009 – Issue 1

Jan 2016

Lean Supply Chain Vs. Cutting Costs to the Bottom Line

REFLECTION: FOR STUDENTS: Study Deming’s philosophy, and and observe how critical Culture is to how Toyota dominates long term.

FOR ACADEMICS: Teach how interconnected organizations are more resilient than silo shaped organizations

FOR PROFESSIONALS/PRACTITIONERS: If Top Management is using Lean incorrectly for short term financial savings, demonstrate using COPQ how the Hidden Factory is damaging the company under the disguise of “Lean”. If they still will not react strategically, search for other employment, as the more valuable you are to the company, the more easily you are converted into short term savings. Cutting the experienced and hiring those fresh out of school with little to no experience is a quick way to claim “savings”. Replacing the years of lost experience by training the new employees and paying for all their errors is a massive expense.

The Goal of Lean Management

Some (especially top management and supply chain) misinterpret lean as the ability to do more with less by eliminating waste and decreasing costs.

This idea of Lean often leads to two critical issues-

1. Companies cutting labor that is no longer “needed” to “reduce waste” so they can “do more with less.” It is a fancy way of telling the rest of the company employees to work harder to take up the slack for all the people I just fired and is very damaging to buy-in. Companies lose tribal knowledge that the company was unable to capture, and new learning costs are incurred when the costliest employees are cut to save money (and it is a frequent occurrence when Lean is used for cost-cutting).

2. Supply Chain chooses suppliers based upon financials, and OTD, not supplier quality. Lots of promises and preliminary approvals that drag on and on. You get what you pay for. Low cost frequently equates to low quality. If a competitor knows their product is better, they will raise the price because others will want to buy it. Cheap suppliers look good for the first quarter, but when the hidden costs of rework and recalls hit, somebody has to be held accountable.

Was it Quality’s fault? Supply Chain’s fault? No. It was the Administration was accountable for allowing the hidden factory back into the culture. Supply Chain especially should be able to understand when the QM tells the board that we need to invest in better suppliers. The goal of Lean management is to maximize customer value while minimizing waste. Allowing rework into the factory through the supplier is a total waste of resources, and it can cost a lot of money, time, and, frequently, loss of reputation in the eyes of potential customers. Investment in your company brings long term gains, not slashing people and resources.

It is also essential to set up an APQP/PPAP process that matches the needs of all the stakeholders. Two main factors to consider are the expected Volume of orders for the product or service and the Variety of products / and services. With products of high levels of variety (such as frequent custom orders) with relatively low product volume, Agile Project-type planning control is most effective. Low variability (not much change customer to customer), but substantial orders, would bring about a need for lean planning.

Conclusion

Lean is not a tool to be used like a Machete to “cut the fat” quarter to quarter. Eventually, while you are hacking at the perceived “weeds and vines” you will cut your company’s foot off and some of your foundation will be lost. Add value and eliminate waste carefully by categorizing value and waste as a team.

How Software Quality Engineering and Design Quality Are Similar

REFLECTION: FOR STUDENTS: If your education looks as if it may lead to a point where you have interactions that involve a QMS, be sure to pursue at least a basic understanding of software, as that understanding will be gold in all future industry employment.

FOR ACADEMICS: AI and ML are coming, but it will be a while before any doctors or engineers are actively replaced, but it would be wise to teach your students how to think for yourself, not just rely upon the computer. Teach students to be the person who writes the program or qualifies the program, not the person who is told by the computer what to do.

FOR PROFESSIONALS/PRACTITIONERS: Learn all you can about the software world if you have not yet. If you are purely a Software Quality Engineer, get as much exposure to other quality systems to help open your mind up to different problem-solving pathways. Always be a lifelong learner.

Definition of Quality

There is no single definition of quality that has ever or likely ever will be agreed upon even in a single company, much less an entire industry or across industries, but the ISO/IEC/IEEE Systems and Software Engineering-Vocabulary (ISO/IEC/IEEE, 2010)

provides an excellent layout of every aspect of defining quality.

- The degree to which a system, component, or process meets specified requirements

- The ability of a product, service, system, component, or process to meet customer or user needs

- The totality of characteristics of an entity that bears on its ability to satisfy stated and implied needs

- Conformity to user expectations, conformity to user requirements, customer satisfaction, reliability, and level of defects present

- The degree to which a set of inherent characteristics fulfills requirements

Each organization must decide what quality is, however, only a world-class organization will always be using the feedback from all stakeholders to evolve the organization’s definition of quality so that stakeholders are satisfied at every level.

Changes Are Coming

I have written a couple of posts about how Quality 4.0 and Industry 4.0 are here. However, based upon the fact that the Quality industry is in many areas still building the foundations of a Quality culture that will support Quality 4.0, there are likely to be many quality professionals who fall into one of three major groups.

Some may be in a state of denial or unawareness of the exponential growth level of the emerging technology and believe things will stay the same as they have for all these years. The next group is made up of those who are fully aware of the changes that are coming. The members of this group and are getting ready for the inevitable change. The last, and most likely smallest group (though I have no formal data, shame on me), would be those who know what is coming but actively do not want the change to occur.

The reason I believe that would be the smallest group would be the fact that the vast majority of quality professionals are problem solvers, change agents, and not comfortable with things just staying as they are. The old “If it isn’t broke, don’t fix it” axiom is the antithesis of the Quality mindset.

Software Quality Engineering

In the past few years, I have witnessed the medical device industry evolve rapidly. A few years ago, I saw DHFs (Design History File), DMRs (Device Master Record), and DHRs (Device History Record), all kept on paper in files in a locked room and carefully controlled. Quickly the entire paradigm shifted to Cloud storage of these documents with ultra-tight security, in addition to management of routing of document approvals moving from physical signatures to electronic signatures. I also witnessed software become officially regulated as medical devices (SaMD).

Software Quality Engineering is- The study and systematic application of scientific technology, economic, social, and practical knowledge, and empirically proven methods, to the analysis and continuous improvement of all stages of the software life cycle to maximize the quality of software processes and practices, and the products they produce. Generally, increasing the quality of software means reducing the number of defects in the software and in the processes used to develop/maintain that software (WestFall, 2016). Software development usually uses an Agile project management approach. Agile project management seems to draw heavily from the Lean philosophy, which focuses on creating better customer value while minimizing waste. Both philosophies emphasize fast deliverables. The emphasis of Lean is on reducing waste and unnecessary steps; however, Agile emphasizes breaking large tasks into small ones and delivering in short sprints. Both Lean and Agile use some sort of an action loop. In Lean, this is the build-measure-learn cycle, while Agile’s scrum methodology uses an iterative sprint approach (L. Allison Jones-Farmer, 2016).

The iterative steps used as part of the Agile Scrum methodology help prevent excessive costs. When a defect is not caught early in the development of software, the defect can impact many more aspects of the software. The later in the life cycle the defect is detected, the more effort (and therefore expense) it will take to isolate and correct defects. A single defect in the requirement phase may have a “butterfly effect” and cause exponential levels of cost as the defect goes undetected.

At the end of each iteration, the goal would be to have a working example demonstratable for stakeholder review and feedback so that any issues with correctness or quality can be addressed in the next iteration (WestFall, 2016).

Traditional Design Quality

Design Quality from the manufacturing perspective aligns closer to Crosby’s viewpoint of the need for a well-defined specification against which to measure quality. One of the things about the fast-changing Quality world is that software is less about the reproducibility to spec and more about innovation. As the manufacturing world has found itself thrown into a massive acceleration in the last few decades, traditional design perspectives have been re-evaluated. Engineering tools like TRIZ have been employed to help spur innovation in design and problem-solving. Design For Six Sigma (DFSS) shifted product design away from just doing it right the first time toward robustly employing QFD to obtain the voice of the customer. The best DFSS process for a new design (in my opinion) would be the IDOV method- Identity (obtain VOC & CTQs), Design, Optimize, Validate. At the Validate stage, a prototype is tested and validated, with risks thoroughly analyzed (and as required, sent back to an earlier stage if validation is not accepted) (Kubiak, 2017). I have seen more and more manufacturing operations learning to use agile methods for design, frequently combining Agile with Lean, Six Sigma, or Lean Six Sigma depending upon the culture and knowledge base. It is clear that as software, apps, and AI become integral parts of product and production, the pace at which innovation must occur to meet customer requirements will continue to grow, perhaps eventually leading to a permanent fusion of Agile, Lean, and Six Sigma.

Conclusion

There are many other methodologies out there, like the waterfall mythology, which has lost a bit of popularity over the past few years to Agile methods, as well as CMMI, which I have heard conflicting reports on how compatible CMMI is with Agile. I would appreciate input from those in the software industry who can tell me firsthand how well CMMI and Agile work together. Software DevOps is effectively designing a product for stakeholders from ideation to operational release and monitoring/maintenance. Designing a physical item to sell on the market based upon the VOC using a QFD may be slower and use a more thorough investigation of the requirements and desired outputs (since you are addressing something tangible rather than an idea for a program). An idea that can provide value (software) is much harder to define in a neat specification box. Still, just like a DOE, you keep adjusting your settings and continue trying until you determine what factors are critical. Then you optimize the settings for your critical factors to obtain the best outcome based upon cost, functionality, and VOC. If you are worried about the coming changes, do not be worried, embrace the change, and be part of the change. Yes, in 20 years, we will all be behind a computer console writing code (if AI has not replaced al the Quality Engineers), but as long as you are looking forward, you will be moving in the right direction.

Bibliography

ISO/IEC/IEEE. (2010). ISO/IEC/IEEE 24765 Systems and Software Engineering. Geneva, Switzerland: ISO New York, NY.

Kubiak, T. a. (2017). The Certified Six Sigma Black Belt Handbook Third Edition. Milwaukee: ASQ Quality Press.

L. Allison Jones-Farmer, P. T. (2016, 10). asqstatdiv.org. Retrieved from ASQ: http://asq.org/statistics/2016/10/agile-teams-a-look-at-agile-project-management-methods.pdf

WestFall, L. (2016). The Certified Software Quality Engineer Handbook 2nd Edition. Milwaukee, WI: ASQ Quality Press.

How to Communicate the Cost of Quality (COQ) In a Way Top Management Understands

REFLECTION: FOR STUDENTS: Use your business and management classes to prepare you for Improvement Project management. Nothing happens in a business unless it is profitable.

FOR ACADEMICS: If you are teaching Project Management be sure to teach more than “Top Management must support your team”. It will help greatly if team members understand why top management must buy into a project, as the economic model cannot be explained at the beginning of every project.

FOR PROFESSIONALS/PRACTITIONERS: If your organization finds itself in a silo mentality between production, quality and management, always use cost as the negotiating method. Hard dollars are not subjective or debatable.

What is the Cost of Quality?

I use the term Cost of Quality because the common term Cost of Poor Quality (COPQ) seems to fail to capture all the efforts in the quality metric that should be communicated to Top Management.

For many years there was a lack of understanding between the production and quality department. Quality usually knew when a process was wasteful, but production was not particularly concerned with operational excellence. The prime metric from a production standpoint was, “How many widgets did we produce this shift?” and “Did it meet our Quota?”. The scrap costs and rework costs were hidden deeply in the metrics, not because the data did not exist, but because the data were not being actively tracked. Top Management frequently was blind to the full cost of all the quality efforts and failures that were occurring during production (or even design quality costs).

This lack of communication led to the infamous “Hidden Factory” effect that drove the first wave of modern Quality Guru’s to try to bring Quality to the forefront of Business consideration. Taguchi, Crosby, Juran, Deming, Ishikawa, and Ohno all had similar views on waste, though they did not all have the same philosophies.

The end result was: After many years, the Culture of Quality and Change Management has become more the norm (though there is still far to go in many areas). Most Top Management has a language with which they can talk to the Quality and Production departments and can share, and that language is Dollars. Top management had always wanted a bottom-line impact report. It was not genuinely concerned with what Quality had to say until Quality started talking about lost dollars that impacted the bottom line.

Since the actual cost of producing a product to spec is approximately 15% for manufacturing firms, varying from as low as 5% to as high as 35% based upon product complexity of total costs, it presents a clear opportunity to cut the bottom line for reducing these overall costs (Joseph M. Juran, 2010) (Bill Wortman, 2013).

There are three primary categories of Quality Costs categorization: Prevention, Appraisal, and Failure. Once your organization has a firm classification of these costs, choosing to document the quality costs will provide project managers with a way to measure and prioritize Quality Improvement projects. Peter Drucker is credited with the obvious truth – “If it cannot be measured, it cannot be improved”.

Though some individual items such as Audits overlap, this is a useful high-level guide to categorizing your Quality Costs. (Failure has been divided into Internal and External Failures)

- Prevention Costs of Quality- Total cost of all activities used to prevent poor quality and defects from becoming part of the final product or service.

- Quality Training and Education

- Quality Planning

- Supplier qualification and supplier quality planning

- Process Capability evaluation (including QMS audits)

- Quality Improvement activities

- Process Definition and Improvement

- Appraisal Costs of Quality- The total cost of analyzing the process, products, and services

- Document Checking

- Analysis, review and testing tools, databases, software tools

- Qualification of the supplier’s products

- Process, product, and service Audits

- V & V activities

- Inspection at all levels

- Test equipment maintenance

- Failure Costs of Quality- The costs which result from products and services not conforming to requirements or customer/user needs.

- Internal Costs of Failure

- Occur prior to delivery

- Scrap

- Design changes

- Repair

- Rework

- Reinspection

- Failure documentation and review

- Occur prior to delivery

- External Costs of Failure

- Occur after delivery or during the furnishing of the service

- Customer complaint Investigations

- Pricing errors

- Returns and Scrap

- Warranty Expenses

- Liability claims

- Restocking

- Engineering Change Notices

- Occur after delivery or during the furnishing of the service

- Internal Costs of Failure

- (Wortman, 2013) (WestFall, 2016)

Conclusion

Top management support is required for an improvement project.

Any quality dept. will want to improve a process, but for a business, a business case must be presented to top management so they will help remove the roadblocks and provide resources. The quality department must be able to present the estimated ROI (Return on Investment) using the Cost Benefits Analysis to show that there is a viable business case for supporting the improvement project to gain support for the project. Even though improving a process may be the smart thing to do, sometimes it is not the financially viable thing to do at the time. Keep those projects on a back burner and monitor them, though. At some point, some changes may make the improvement much more viable.

Bibliography

Bill Wortman. (2013). The Certified Biomedical Auditor Primer. West Terre Haute, IN: Quality Council of Indiana.

Drucker, P. (1954). The Practice of Management. New York City: Harper & Row.

Joseph M. Juran, J. A. (2010). Juran’s Quality Handbook (Sixth Ed). New York: McGraw-Hill.

WestFall, L. (2016). The Certified Software Quality Engineer Handbook 2nd Edition. Milwaukee, WI: ASQ Quality Press.